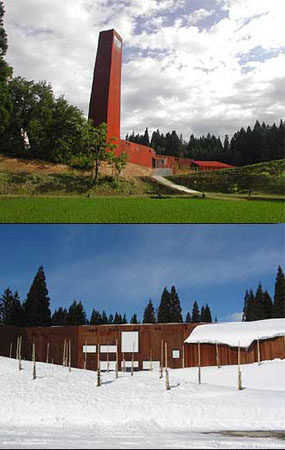

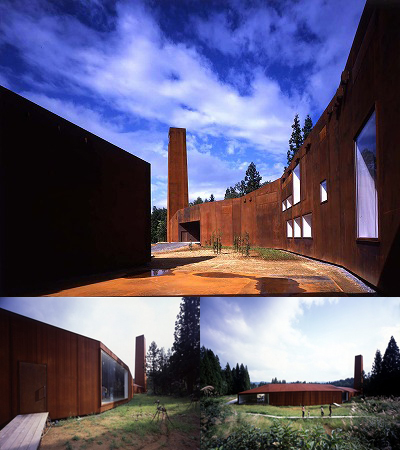

A clear departure from the glass-and-steel structures typical of many Japanese architects today, the heavily armored museum looks more like an industrial relic than a brand-new cultural facility. The building’s irregular form, variegated surface, and absence of highly articulated details all contribute to its unique appearance. “I wanted to make a building that looks like a ruin,” explains Takaharu Tezuka. The museum also represents a new direction in materials and forms for the husband-and-wife team best known for their experimental houses that integrate inside and out.

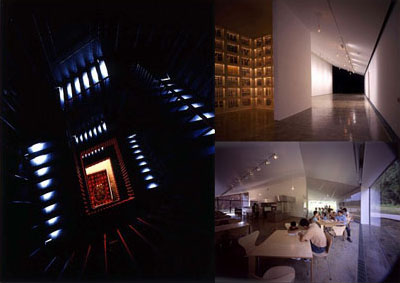

Though the building’s pitched short elevation devices from the profile of the simple sheds that protect local roads from the snow, its plan traces an abandoned path that once linked stepped rice paddies nearby.The building not only replicates the old path; conceptually, it is a path Encased within the museum’s rusting-steel armature, a stark while tube runs the length of the building, narrowing where people walk and widening where they pause to look. Instead of separate galleries, the museum has one long corridor lined with display panels, tanks, and terrariums, and some large images of regional plant and animals projected directly onto the walls. The only discrete gallery contains a donated collection of butterflies mounted in cases stacked from floor to ceiling.

At the same time, the building serves as a place to observe and reflect on the surrounding environment. Framed like pieces of art, floor-to-ceiling views out to the woods, fields, and distant mountains are as important as the artifacts inside. “If you are walking in a forest, you stop and look at many things,” says Takaharu Tezuka. “I wanted to make a building where you can stop and look out.”

The architects inserted the great picture windows where the building bends, so they could open up sectional views in wintertime of compacted snow and any forms of life suspended within it. While designing the museum, they envisioned daylight filtering through loose snow at the top of great snow drifts and seeping inside the museum. Because of the snow load and the tremendous openings-the largest one is 39 by 13 feet-the windows had to be made of 3-inch-thick acrylic, the same material used at aquariums. But acrylic is also three times clearer than glass, which takes on a greenish cast as it gets thicker. The equivalent of triple glazing, the transparent sheets are good insulators whose visibility is not clouded by condensation buildup.

The windows, however, were not the only reason the Tezukas had to look beyond the scope of standard construction technology. Made of steel plates varying from 0.2 to 0.3 inches in thickness, the building’s Cor-ten body required the expertise of shipbuilders to weld it together on-site. To withstand snow loads of 1.5 tons/square meter, a structural steel frame concealed between exterior and interior walls backs up the outer steel shell.

Like a thermos, the building takes advantage of a double skin-in this case, separated by a 22-inch slot of air space where the mechanical system circulates hot air in winter and cool air in summer. A land of climatic extremes, Niigata Prefecture is a place where rugged winters lead to blistering summers, when temperatures can soar to 110 degrees Fahrenheit. “The outside of the building gets so hot you could fry an egg on it,” chuckles Takaharu. Because the building is made of steel, it expands and contracts 8 inches in length each year when the temperatures hit their highs and lows. Instead of connecting columns directly to the foundation, the architects inserted stainless-steel panels between the structural frame and the concrete base, enabling the walls to slide along the length of the building. In addition, grooves-not holes- in the stainless-steel panels allow the bolts securing the columns to glide back and forth. But because it had to be anchored firmly in three places, the building actually changes shape, then snaps back into place.

While man-made interventions were necessary to keep the interior comfortable year-round, the Tezukas are happy to let natural forces have their way outside. In fact, the building’s exterior has already begun to take on the yellowish-red hue of the iron-rich soil. The architects hope that in 30 years the land will return to its unaltered state. To jump-start that process, they enlisted the aid of an ecologist and local volunteers who gathered and transplanted indigenous saplings and seeds to the site. “Our intention was not to make a beautiful landscape, but to restore it,” says Tezuka. Offering dramatic vantage points for visitors to appreciate the snow and scenery, the Matsunoyama Museum underscores that beauty.